James (Jim) Allison, PhD (center), 2018 Nobel Laureate, with fellow scientists, including PanCAN grantee, Michael Curran, PhD (left).

The 2018 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine has been awarded to James (Jim) Allison, PhD, and Tasuku Honjo, MD, PhD. Allison and Honjo are considered pioneers in cancer immunotherapy, which is a strategy to activate a patient’s own immune system to recognize, attack and eliminate cancer cells.

Drs. Jim Allison and Mike Curran both won important awards for cancer immunotherapy in 2010.

Allison is chair of the department of immunology, the Vivian L. Smith Distinguished Chair in Immunology, director of the Parker Institute for Cancer Research and the executive director of the Immunotherapy Platform at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. Honjo is a professor in the graduate school of medicine at Kyoto University in Japan.

The Nobel Prize website states, “The Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine is awarded for discovery of major importance in life science or medicine. Discoveries that have changed the scientific paradigm and are of great benefit for mankind are awarded the prize.”

“Before Jim Allison, most people considered the concept of the immune system curing people of cancer to be a fantasy,” said Michael Curran, PhD, associate professor of immunology at MD Anderson, who conducted his postdoctoral training in Allison’s lab.

Curran, recipient of a 2018 Translational Research Grant from the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network (PanCAN), continued, “It’s thanks to Jim and Tasuku’s perseverance and tenacious approach to research that the field of immunotherapy has become a pillar of modern oncology.”

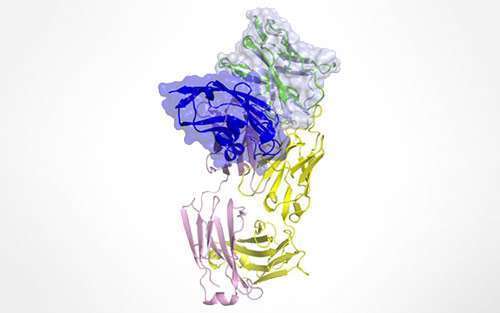

Both Allison and Honjo’s discoveries have focused on overcoming a way that cancer cells can evade an immune attack, through immune checkpoints. Allison discovered a protein called CTLA-4, and Honjo discovered PD-1 – both proteins work to put the “brakes” on an immune response against cancer cells.

A landmark class of drugs, called checkpoint inhibitors, have revolutionized the treatment of some types of cancer. Two of the most successful checkpoint inhibitors, which release the “brakes” on the immune system and allow immune T-cells to recognize and attack cancer cells, specifically block either CTLA-4 or PD-1.

“Undeterred by others’ skepticism, Jim and Tasuku followed the data,” Curran said, “and they succeeded in demonstrating that reversal of T-cell checkpoint inhibition could trigger rejection of both mouse and human cancers.”

In some cancer types, like melanoma, patients have seen remarkable improvements in previously untreatable cases thanks to drugs like CTLA-4 inhibitors that directly stemmed from Allison’s work.

And a well-known PD-1 inhibitor, Keytruda, has been approved by the FDA to treat any type of cancer, anywhere in the body, that displays certain molecular characteristics.

Aside from a small subset of patients who are eligible for Keytruda, pancreatic cancer has been notoriously resistant to immunotherapeutic approaches to date. But researchers, like Curran, and clinicians are striving to develop strategies and combination approaches to bring effective immunotherapy to pancreatic cancer patients.

“In my own lab, armed with the lessons of persistence and rigor learned from my time with Jim, we are striving to understand the roots of immune resistance in pancreatic cancer and how they can be overcome so that more patients can experience the benefits of immunotherapy,” Curran said.