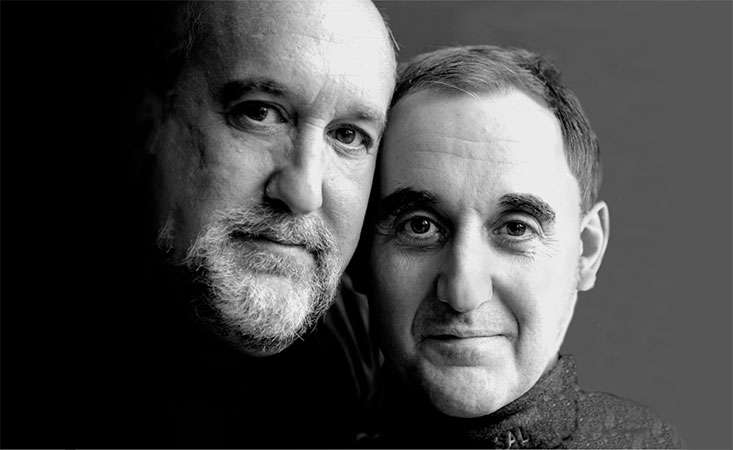

Andy Lyons, at left, and his brother, Steve, who died from pancreatic cancer in 2002

Editor’s note: Today is National Brothers Day. We are sharing this previously published story to celebrate all brothers and the unique bond they share with their siblings.

In 2002, Andy Lyons made his big brother, Steve, a promise.

In a hotel room adjacent to Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago, where Steve had been admitted after being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, he said to Andy, “Please don’t let this happen to you. We need to stop this.”

Said Andy: “I couldn’t agree more.”

Steve died just seven weeks later. And for the next 21 years, Andy has been living out that commitment to his brother, a person he calls “my superman and my hero.”

He’s also channeling the memory of many more beloved family members, all of whom died from the same disease.

“My family has a long, long, long, long history of pancreatic cancer,” said Andy. “My grandmother died from it. And at least two, maybe three of her sisters, and then my mother. And then my mother’s twin sister. And then their brother. And then, finally, my brother. It took me awhile to see the connection, probably because I didn’t want to. But when my brother got it, I just knew it was coming my way.”

Andy wants to determine why his family has been hit so hard by pancreatic cancer. Not only is this a fitting tribute to his loved ones, it also stands help other families as researchers work to understand the complex relationship between a person’s genetic make-up and the disease.

For a couple of years Andy had been getting annual CT scans to check for any signs of cancer, but he felt it wasn’t enough. He started to search for a doctor focused specifically on pancreatic cancer and genetic risk, as the field was in its infancy at the time. Finally, Andy found a familial pancreatic cancer research program conducted by a gastroenterologist who had just relocated to Chicago from Omaha.

To find out if he’d even be eligible for the program, Andy had to go through what usually is an extensive interview but only two questions into it (‘Do you have a history of pancreatic cancer in your family?’ ‘Well, yes I do.’ ‘Are you of Eastern European Jewish descent?’ ‘Yes, I am.’), he was accepted into the study and began regular testing and surveillance.

“The next day I had an ultrasound endoscopy and the doctor took some blood and tissue samples,” Andy said. “That was the start of our nearly 20 years together.”

Then in October 2021, after years of annual trips from his hometown of Des Moines, Iowa, first to Chicago and then Pittsburgh, where his doctor eventually moved, Andy received the news that so many of his family members did. He remembers the moment well.

“My doctor came around the corner in tears,” Andy said. “And two of his nurses were with him and they were in tears. I said, ‘What?’ He said, ‘You have cancer.’”

Because of Andy’s persistence in keeping up with the surveillance, the cancer in his pancreas was detected very early and he was eligible for surgery. He and his wife canceled vacation plans and stayed in Pittsburgh. Two days later they met with a surgical oncologist, who reassured them that since the cancer was caught early, the procedure shouldn’t present any problems “and most likely you’ll be cancer free.”

Andy said he had the surgeon repeat that. Twice.

Since the cancer hadn’t spread, the surgery could be done robotically, which is much less invasive and the recovery time is quicker.

Andy and his wife drove home “very, very fast” and then flew back to Pittsburgh a week later for the surgery. During his three weeks of recovery, he and his wife celebrated both of their birthdays and had Thanksgiving dinner at his doctor’s house with his extended family. Then, Andy returned to Des Moines for 12 rounds of chemotherapy.

At his one-year anniversary follow up, the doctor said there was no evidence of disease and that he had “nothing to worry about.”

“Without a doubt, these annual screenings saved my life,” said Andy. “Early detection is the key. Too often when pancreatic cancer is diagnosed it’s usually in an advanced stage. I didn’t want that to happen to me and I really don’t want that to happen to anyone.”

Andy points to his “vigilance and diligence” as leading to the positive outcome.

“And while part of my reason for doing this was for survival -- I knew the odds of me getting pancreatic cancer were not in my favor and I didn’t want to die – there was an equal if not more important part,” he said. “I’ve got this genetic link in me that’s causing this cancer. Let’s find it and hopefully save a lot of lives. Let’s stop this killer.”

He’s still on the quest, as up until now, researchers haven’t discovered why Andy’s family has been so susceptible to pancreatic cancer. His blood and tissue samples continue to add to that effort.

“I’ve had five genetic tests. And they haven’t found a common marker in me yet,” he said. “I even had one the day of my diagnosis, but they haven’t found one. But you know what? We’re going to, and I’m going to keep going until they do.”

Andy Lyons with his daughter, Laura, and wife, Joan

As he continues with routine scans and recovers from some lingering side effects from the chemotherapy, Andy approaches it all with characteristic good humor. He writes journal entries he shares with friends and family about his time at the “chemo bar” with fellow patients – many of whom have become good friends.

“There were two things that helped me get through this, besides the early diagnosis and early detection,” he said. “A positive attitude and a sense of humor. It was a hard thing to laugh at, but keeping it light really, really helped. That’s pretty much how I’ve approached my life anyway and it has served me well. With my bout with cancer, it served me very well.”

Now, Andy sees it as his mission to help people with pancreatic cancer. Last year he was a speaker at PanCAN PurpleStride Iowa, despite being in the midst of chemotherapy. Friends came from near and far and his team blew way past the fundraising goal.

When he connects with patients and families, his message is one of “vigilance and diligence:” He wants everyone to know signs and symptoms and to advocate for themselves. For those with a family history of pancreatic cancer, he urges them to talk with their doctor about options to help them understand their risk.

“Get yourself checked out. We’ve been taught to run away from cancer, or ignore it, or don’t talk about it,” he said. “And where does that get us? No place. A late diagnosis with a bad prognosis. So I say don’t run from it, run at it. Get proactive. It can save your life. It did mine.”

His brother’s words live on.

“What my brother told me is really for everyone,” Andy said. “We can all help to end pancreatic cancer.”