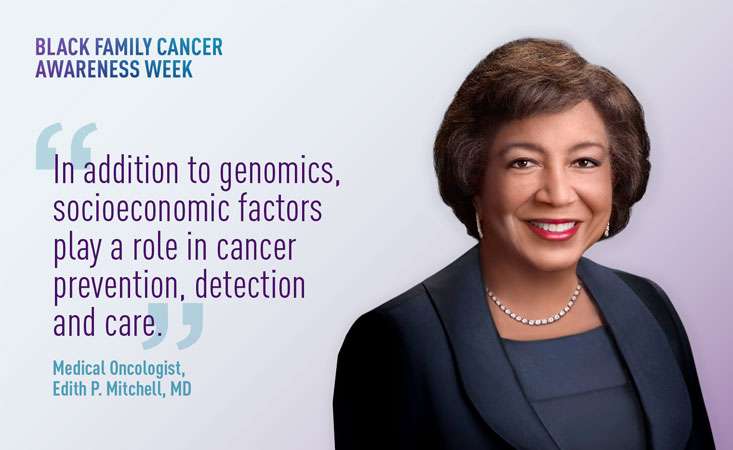

Editor’s Note: We are saddened at the passing of Dr. Edith Mitchell on January 21, 2024. She was a trailblazing oncologist and cancer researcher, advocate for healthcare equity and dear friend of PanCAN. PanCAN sends deepest sympathies and heartfelt condolences to her friends and family.

Edith P. Mitchell, MD, is a medical oncologist treating pancreatic cancer patients at Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. She has devoted her career to an area of personal interest – healthcare equality.

An estimated 60,430 Americans will be diagnosed with pancreatic cancer this year. Black Americans have the highest incidence rate of pancreatic cancer of all ethnic/racial groups in the United States, according to the National Cancer Institute SEER data.

PanCAN: Dr. Mitchell, what or who inspired your career?

Dr. Mitchell: My interest in medicine and disparities started at 3 years old, on the day my great-grandfather became ill. I overheard, “You can’t take him to the hospital because they don’t take care of Black people.” There was talk of him not being assigned to a bed if he went…that he would be sent to the basement. Luckily, a family physician made house calls and he came to our house, his big black doctor’s bag in tow.

I thought he was impressive. I told my great-grandfather that when I grew up, I wanted to be a doctor to make sure he got good healthcare. He said, “You can do whatever you want, as long as you plan and work hard.”

So I started working on that plan when I was 3.

I remember looking at children’s books with pictures of doctors and their black bags. As the years went on, I read everything that I could about medicine. When I went to college and medical school, I kept my great-grandfather’s story in mind. I wanted to not only be the best doctor I could, but to also make sure everyone had equal care.

PanCAN: Why do pancreatic cancer and other diseases affect people of color disproportionately?

Dr. Mitchell: We still have a lot to learn about the biology of cancer, and we need more genomic profiling of tumors so that we can develop better preventive and treatment strategies. But in addition to genomics, socioeconomic factors play a role in cancer prevention, detection and care:

- Greater exposure to carcinogens in the air, water and soil in underserved communities

- Lack of fresh fruits and vegetables in the diet because quality fresh food is not available or affordable

- Lack of access to quality healthcare

- Taking time off work (and therefore not getting paid) to go to the doctor is not an option

- People may have to rely on public transportation to go to the doctor so they’re not only losing money by taking time off work, they may have to take many different routes or buses, so it’s time-consuming and difficult

- Lack of trust in the healthcare system

- Lack of knowledge about pancreatic cancer symptoms, which can mean a later-stage diagnosis and limited treatment options

PanCAN: What are some ways you help patients who live in medically underserved communities?

Dr. Mitchell: I call my approach the “Edith 360.” In addition to asking about their medical condition, I go full-circle and ask my patients questions about their home, community and local resources.

I had a pancreatic cancer patient who lived in a disparate area of Philadelphia and I asked her how she was getting along. She confided that she had to leave her job because of her cancer, that she lived alone and that her income was suspended while she waited for her disability insurance to come through.

I said, “What are you doing for food?” And she said, “I’m not.”

I connected her with a food program through our social services group, and they started delivering food to her home.

I’ll also ask patients how they arrived for their visit and if they need parking passes for free parking at the cancer center or other transportation assistance. We don’t want them to have to spend an hour and a half on public transportation getting to and from their treatments.

PanCAN: What are steps healthcare professionals can take in their communities to mitigate healthcare disparities?

Dr. Mitchell: We all should know our community where we practice so we can fill in the gaps. Here’s one example of how to do that: Make sure there can be a discussion between doctor and patient in the patient’s preferred language. Sometimes the person in the family who is translating may not translate accurately or in a way that the patient can understand.

Also, getting back to the “Edith 360” approach, it’s important to form a compassionate circle around the patient or family so they develop trust in their healthcare and their team.

This level of trust-building extends to research and clinical trials. When you look at clinical trial statistics, people of color are participating in clinical trials at a much lower rate – Black Americans make up 13% of the U.S. population but only represent 3% of clinical trials participation. We have to help patients understand the importance of clinical trials – and the safety of trials – so that people of color are more willing to participate and understand the benefit.

PanCAN: How can an organization like PanCAN help address equity in healthcare? How can the public help?

Dr. Mitchell: I’ve been working with PanCAN for many years – at least 15! – and I really appreciate the work PanCAN does with patients, healthcare professionals and researchers.

Collaboration is key and it’s something PanCAN does well. We all have to work together and form a big umbrella of broad support, care, information sharing and research progress for patients. We’ll have a stronger force that way.

As for how the public can help, it really does take a team effort. I’m committed to increasing diversity in the workforce – as I mentioned, Black Americans make up 13% of the U.S. population but of practicing clinicians, only 4.8% are Black and that has not changed significantly in decades. In communities of color, these are the healthcare professionals people trust. So, for educators and parents, I think it’s important to encourage high school students in these areas to seek careers in science and medicine – clinicians are needed and researchers, too. In communities with lower socioeconomic status, kids may not understand they can be cancer researchers and clinicians. Scholarships for these students are important, as well as mentoring.

We can all do so much more if we’re working together and moving in the same direction.

PanCAN: Your great-grandfather would be proud of the work you are doing.

Dr. Mitchell: Before he passed away, he made sure family members knew he wanted me to have his chair. It was special to him – his mother gave it to him in 1889, the year he got married. Today, doing this interview from my home library, discussing the urgent need for equality in healthcare and remembering the reason I chose this path, I am sitting in that chair.